Teaching Community Engaged Conservation in the UCLA/Getty Conservation Program

Written by Fiona Dunlap

Conservation students spend years mastering materials, methods, and ethics, but learning to work with people associated with cultural heritage is a relatively new area of conservation education. Nicole Passerotti, Director of the Andrew W. Mellon Opportunity for Diversity in Conservation/Conservator, and Anya Dani, Director of Community Engagement and Inclusive Practice / Lecturer, understand this challenge. In the winter of 2025, Dani and Passerotti co-taught the course Conservation and Community, not only to build students’ confidence and skills as emerging conservators but to make them better community partners. “It can be jarring to go into the world and try to work with communities if you are only drawing on textbooks and standard classroom experiences,” explains Passerotti, “you may hit a wall or [accidentally] shut down a conversation because of idealized expectations.”

To move from theory to practice, they partnered with La Historia Historical Society Museum in El Monte, California. As the main focus of the course, Passerotti and Dani trained and empowered students to plan and execute a two-day community conservation clinic that the students named Tu Historia: Caring for Family Treasures. A community conservation clinic is an event meant to support people to care for their own meaningful objects. In real-time, students were shepherded through the process. The students shared their own stories, gave presentations and consulted on preservation and conservation techniques that community members could accessibly use. Community members brought personal treasured items to the clinic to discuss their significance and learn about caring for them. Just as importantly, the event also became a space for students to learn—discovering how the community cares for their family heirlooms in deeply personal ways, regardless of conservation standards.

Dani and Passerotti spent months building the framework for the course. They spoke with potential community partners, assessing their needs. With La Historia, they had an open discussion about the constraints and benefits of collaborating with a class on the brief, ten-week quarter system. An unexpected, yet ideal opportunity arose through a common connection. Ronel Namde, Associate Conservator in Photographic Materials from the Getty Museum, who had an existing relationship with La Historia, first connected Dani to La Historia’s Bianca Sosa-Phal, Community Archivist and Museum Director Rosa Peña, long-time community volunteer and La Historia’s Board President. Ordinarily, the first meeting with a community organization consists of listening to their needs, wants, and histories, but Dani recounts, “the meeting went so well that towards the end I tentatively mentioned that we were planning to teach a class in the winter, and were exploring the idea of a conservation clinic. ” For Sosa-Phal and Peña, the conversation came at the perfect moment. “Rosa and I had just been talking about how we wanted to offer the museum/archive space not just as a place where records live, but as a space for community gathering, learning, and knowledge sharing,” recalls Sosa-Phal, “I asked Anya [Dani], ‘why don’t we have the clinic here?’”

With a partner to structure the course with, Passerotti and Dani’s next step was to prepare the students for the clinic. For the course, this meant preparing lectures, compiling readings and resources, having guest speakers with specialized knowledge, and sharing tangible examples of what the students might come across while working at a community clinic. The preparation went beyond mere hand skills, into the ethics and techniques involved with working with communities. Dani mentions the necessity for students to practice observing their own biases and developing cultural competency. They needed to build an understanding of and sensitivity towards the community they were entering, which was largely Mexican American. Students had to understand that “we’re all coming from a particular angle, and it’s hard to know how your point of view might differ from your collaborator. It means we have different perspectives to bring to collaborations.”

While transferring knowledge to students through readings and lectures is an important pedagogical strategy, learning by doing can be even more impactful. In this case, the students managed much of the planning of the conservation clinic at La Historia under the instructors’ supervision and in close contact with the community partners. They communicated with Sosa-Phal and Peña to plan the event. They also made bilingual flyers and handouts, developed presentations and demo stations, and selected local caterers for refreshments. This level of initiative was rewarding, but it proved challenging during the brief period of a ten-week course. Dani and Passerotti admit that in the future improvements could be made in communicating clearer expectations to the students. Passerotti explains that “it was challenging. We asked them to do a lot in a short amount of time, with the goal of preparing them to be more flexible, adaptable, and good listeners when working with communities in the future.” She could see their “confidence grow with time, especially when they realized this isn’t a test, this is real life.” To ensure the needs of the community and La Historia were being met, the students engaged in discussion with Sosa-Phal and Peña. For instance, Sosa-Phal explained that the conservation clinic idea had started as a single-day event, which she knew “wasn’t enough time for the community to trust [visitors].” Therefore, from early on there was an expectation for a two-day event. Sosa-Phal also explained that the students developed improved collaborative skills as the quarter progressed. Students learn that meaningful collaboration isn’t just about offering options—though that is important—it is also about inviting the community to shape the event itself. For example, initially, student suggestions sometimes took the form of, “this is what we want to do, are you guys okay with that?” However, during the process of planning, they learned that meaningful collaboration means not only asking about preference, but also what the community wishes to contribute. In the end, students worked to make this event a space where community voices, stories and ideas were part of the process.

Figure 1. Building trust is a necessary step in caring for a community’s cultural heritage. Here, Hattie Hāpai presents an item, emphasizing the emotional importance cherished items carry.

The clinic took place at La Historia on two consecutive Saturdays. With the first day finally arriving, the students were nervous, feeling responsible for the event’s success. The task of consulting with community members on the care of their personal treasures felt daunting, but Passerotti explains that this is customary when working with community partners. “It’s pushing through that discomfort and finding a connection” that matters. “Working in a community museum, like La Historia, makes you pause and think, okay, what is useful to them? What information can I offer?” Sosa-Phal and Peña emphasized the need for the event to be accessible: “if you’re here to educate, educate in terms that are going to be easy for the community to understand.” The focus needed to be on using tools that many already had at their disposal, “not buying a $300 chemical to clean your jewelry.” Furthermore, students needed to demonstrate patience and understanding in their community interactions, which is a key to slowly building trust.

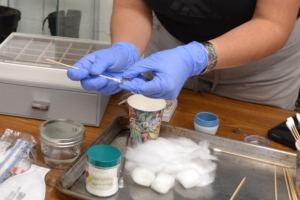

Figure 2. During Tu Historia, students suggested accessible ways to preserve cherished items. In the photo above, Rachel Moore demonstrates how to care for tarnished silver.

The start of the student presentations exemplified an integral aspect of building trust. Each brought in their own personal objects to present on, allowing community members to know the cohort and build trust between them. Sharing their own meaningful items helped establish common ground with attendees and emphasize the deeper emotional value of preservation. That vulnerability opens the door for connection, which is necessary when conservators treat or advise on treasured items deeply enmeshed with personal histories.

On the second day, during the consultation process, the students were expected to come to their consultation from an accessible perspective, ensuring that the average person could follow through with their recommendations. On this second day, the students and participants were able to build a relationship, and by the end, “there was a lot of laughter and it didn’t even look like a clinic. It looked like a couple of friends who got together,” explains Sosa-Phal. The connection left a lasting impression upon the students. Paige Hilman shares that “It was great to be able to bring conservation and preservation discussions outside of the museum and academic environment. I especially enjoyed getting to chat with the community members about what brought them to the event, their roles as family historians, and their relationship with El Monte and La Historia. While event planning has its challenges, these discussions with attendees made it all worth it. I hope to continue pursuing opportunities to bring conservation and community together.” Similarly, Fernanda Baxter emphasizes, “this experience has deeply influenced the way I approach community engagement and taught me the importance of shared ideas and collective action, where every voice is valued, and the needs of the community take precedence over individual agendas.”

When it comes to troubling inequities, conservators, university educators, and larger cultural institutions must not approach community work by “talking down to communities or putting yourself above them, but treating them as partners,” emphasizes Dani. Rosa Peña expands upon this idea, stating that emerging conservators must “be humble enough to listen to what the community has to say and respect the way they have preserved their stuff.” In Anya Dani’s own words, “conservation can be used to uplift communities, especially marginalized communities who have been told that their culture doesn’t matter.” The reality is that marginalized communities have been practicing preservation in their way, often because no one else would. This is a reflection of societal and academic systems’ problematic hierarchies that dictate what and whose culture deserves to be preserved or whose forms of preservation are legitimized. The result is communities becoming custodians of their histories, transforming homes into archives reflecting generations of proof of existence. Within these archives, even banal objects carry meaning through their connection to the community and past generations’ resilience.