From Neem leaves to Sustainable Futures: Dr. Elizabeth Salmon on Preventative Conservation

Salmon at the 2024 doctoral hooding ceremony at Royce Hall, after earning the first PhD ever conferred by UCLA in Conservation of Material Culture. (Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Salmon)

Since 2004, the UCLA/Getty Interdepartmental Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage has shaped the next generation of conservators, equipping them with the expertise they need to excel in the field. Meet Dr. Elizabeth Salmon, the inaugural graduate of the PhD program and Preventative Conservator at the Balboa Art Conservation Center (BACC) in San Diego, California.

Salmon discovered art conservation during her senior year studying Anthropology at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. Following her graduation, Salmon worked as an intern in the scholarly programs and publications department of the National Museum of Asian Art. During her time there, she remembers “telling anyone who would listen that I was interested in conservation.” Aware of her enthusiasm toward conservation, a staff member invited her to participate in a learning opportunity focused on conservation of wall paintings at the Leon Levy Foundation Center for Conservation in Nagaur, Rajasthan. Having already studied abroad in India, this opportunity was all the more exciting. Salmon recounts, “it was my first conservation experience, and it was just amazing. It made me want to go back and prepare to apply to graduate programs.”

When choosing a program to further her education, Salmon explains, “it was always UCLA for me.” At the time, the UCLA/Getty program was the only conservation graduate program in the U.S. that didn’t require applicants to study French or German as their second language, which she explains “was a no-brainer for me. I knew I wanted to work in India and my hometown of San Diego and those languages wouldn’t help me work in those communities.” The UCLA/ Getty program encourages students from varied backgrounds to work on projects that reflect the richness and complexity of cultural heritage on a global level. The program’s interdisciplinary approach allowed her the ability to embed diverse conservation practices from the start. Additionally, UCLA’s proximity to institutions like the Getty Center and Villa, as well as the Fowler Museum, allows students the opportunity to consult with conservators and scientists and have access to their facilities and collections. The UCLA/Getty program requires each student to have a thesis or dissertation topic to research, meaning students “contribute to the field while in training.”

In 2015, while Salmon was a collections care and curatorial intern at the Mehrangarh Museum in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, she was tasked with changing out neem leaves for pest management. “I had never heard about museums managing pests in that way,” she said. Later, while working as a Research Associate at the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training in 2018, she was introduced to Ellen Pearlstein, a Professor in the UCLA/Getty program, to talk about her interest in the newly established PhD program at UCLA, which would welcome its first students the following year. Pearlstein asked, “if you were to study in the PhD program, what would your research topic be?’’ Reflecting on her initial conversation with Pearlstein, Salmon shared, “I wasn’t expecting to discuss research topics in this first conversation but immediately thought back to that memory of seeing museums in India use neem leaves for pest management, which always stuck with me as an innovative approach to caring for collections” to which Pearlstein replied, “that’s really fascinating, and I think it would be a great project.” What started as a moment of curiosity evolved into a central theme for her dissertation.

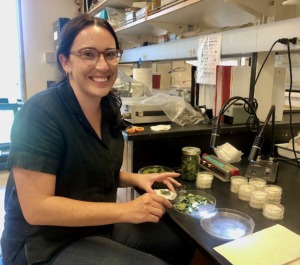

Salmon setting up experiments to test the effects of dried neem leaves on carpet beetles, a common museum pest. (Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Salmon)

The neem plant is traditionally used for pest management in India. Neem is a natural insect repellent that is used in homes and some museums to prevent insects from eating textiles, causing damage and loss. In her initial literature review, Salmon explains that while entomological research had established that the active ingredient in neem, Azadirachtin, was indeed effective in repelling certain insects, the only information she found pertaining to heritage preservation was a few brief references to neem that, in summary, said, “ dried neem leaves are stored with textiles to prevent pest damage. It appears to be highly effective.” As she succinctly put it, “it doesn’t give this method of traditional conservation, which was refined over time and across generations, the consideration it’s due.” Salmon sought to fill this gap and to document the advantages and disadvantages of this traditional method, with an emphasis on preventative conservation and sustainability. She observed the material properties of neem and its effects on textiles, ensuring it didn’t adversely affect the textile it was stored with. The next objective was to perform tests to document neem’s effectiveness on carpet beetles, a notorious museum pest. Through her research, she found that even in a closed chamber, neem leaves reduce the amount of textile that the insects eat without killing them. She explained, “we don’t need to kill the bugs to have effective pest management in museums, and really, it’s not the most environmentally conscious thing for us to do, right?”

The idea of limiting the intervention conservators might have to do is integral to preventative conservation. Salmon explains that “preventive conservation is about taking our choices out of the equation as much as possible and instead focus on creating an environment that supports preservation to help the objects live as long as possible without direct intervention.” Preventive conservation also provides a sustainable angle through its long-term cost-effectiveness, especially for small institutions that might not have the funds to pay for conservation treatment for their objects. In fact, the monetary ability of an institution to pay for treatment reveals a troubling fact about collections. She explains that “the money is at these larger institutions,” begging us to question, “who is deciding what cultural heritage is worthy of conservation treatment?” Preventive conservation can help limit these biases, by allowing more cultural heritage to be preserved in a cost-effective and sustainable way.

This year is the Balboa Art Conservation Center’s 50th birthday. Though they historically focused solely on the conservation of paintings and paper, in the last two years, BACC has added an objects conservation department and a preventative conservation department, the latter of which Salmon is the inaugural steward. The inclusion of these departments reflects an intentional shift for the regional center, as it allows them to work with a wider range of communities that need their objects conserved. She asserts that “our duty is to serve the whole community.” As a Preventive Conservator at a regional conservation center, Salmon oversees conservation projects from the entire western region of the United States, which includes advising museums and private clients on a number of issues related to proactive collections care and also teaching workshops. She explains, “we want to empower people to do more collections care and preservation by sharing our knowledge to support that work.” In addition to the responsibility of founding the new preventive conservation department at her organization, it can be challenging to persuade institutions to implement preventative conservation practices in the stewardship of their collections. She adds that sometimes “people don’t want to spend the money to prevent a problem. It’s a challenge, but one I signed up for. And it’s exciting too!”

Working at a regional center has allowed her to develop deeper connections with local communities, which is particularly meaningful for Salmon, who is working in her hometown of San Diego. Salmon expressed her excitement “to bring communities into our labs and look at their art and cultural heritage together, but also say, ‘do you want to look at something more closely? Let’s look at it under the microscope, let’s look at it under UV light or step into the imaging suite and look at it with X-ray fluorescence to see how that might answer your questions’.” With the knowledge and tools conservators have at their disposal, it is also integral to emphasize community-based practices, knowledge, traditions, and histories, something that Salmon incorporates into her practice. She emphasizes that “people with different sources of knowledge must work together for the preservation of cultural heritage.” She believes that conservators should remain fluid in their approaches to preservation and emphasize sustainable and diverse approaches to problems.

Looking forward, Elizabeth Salmon implores future conservators to “be true to yourself … It’s diverse stories and diverse backgrounds that are going to be a complete game changer in the field…you can always learn the science, but that other part – how your story informs your perspective – cannot be taught in a graduate program.”